N.Ariuntuya

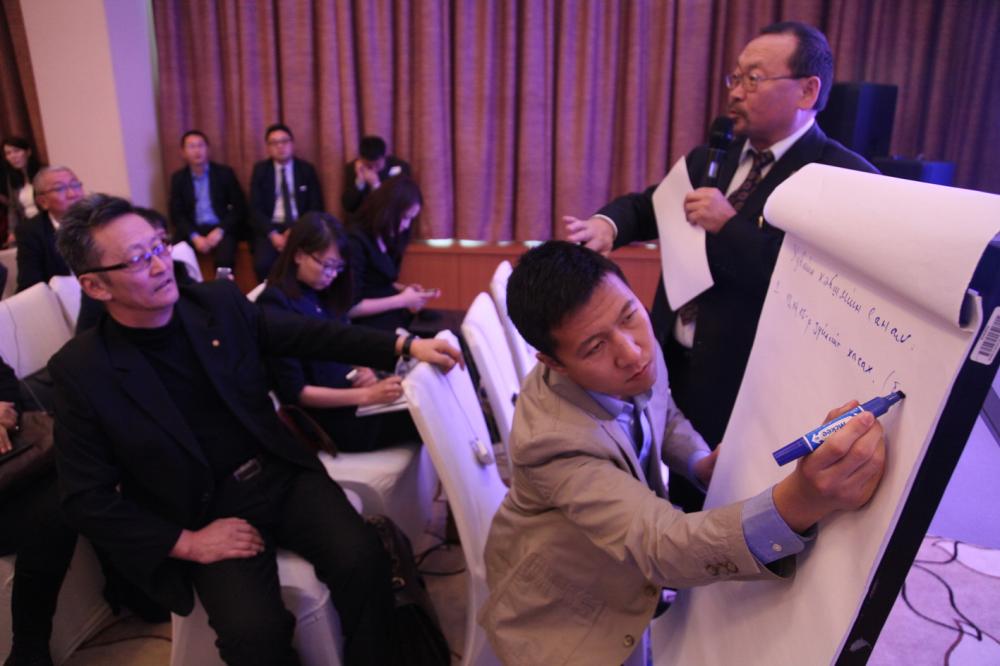

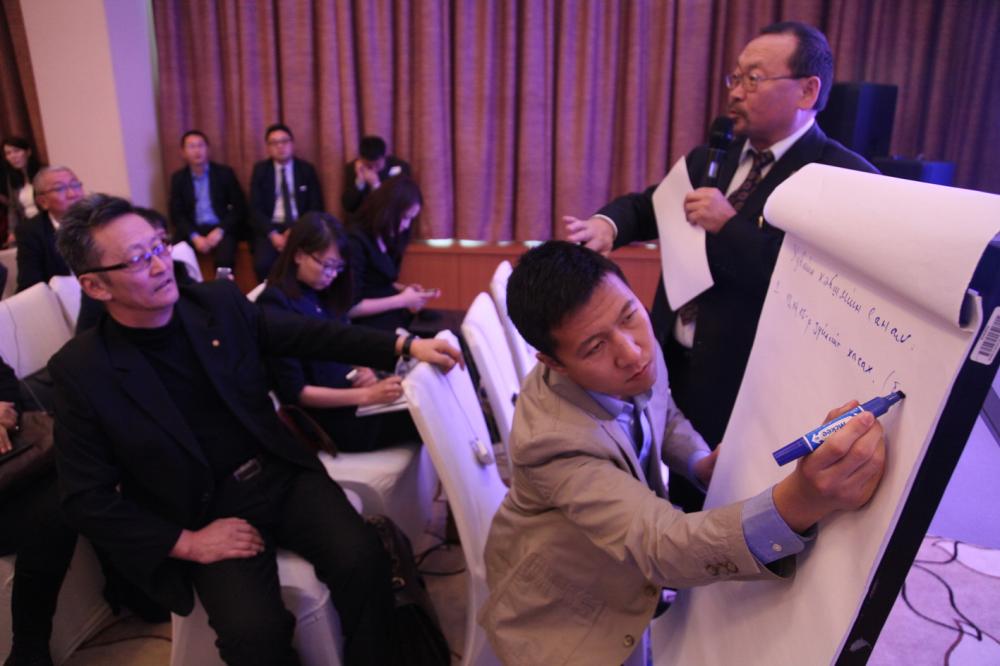

The importance attached to the discussion of the Draft Mineral Law on January 18 was obvious from the fact that the venue, a meeting room on the 3rd floor of Blue Sky Tower, was full half an hour before its scheduled start at 9.30 am. Among the 300 or so eager people in attendance, one could see officials from ministries and agencies, executives of mining companies, foreign investors, lawyers, herders wearing the deel, and women who said they represented small-scale mine workers in the aimags.

There was B. Delgersaikhan of the Bold Tumur Eruu Gol, who is rarely seen at any public event. Among scientists and academics could be seen Drs D. Dondov, N.Dashzeveg, S.Avirmed, and Kh.Vladimir. J.Zanaa from the civil society was there, and many looks were reserved for P.Davaanyam, who claims to be a direct descendant of Chinggis Khaan.

Two former Prime Ministers were there. D.Sodnom was an early arrival and would stay to the end. The other, D.Byambasuren, would come around noon, and give a serious speech on the proper legal environment for the mineral sector. It was, thus, a unique gathering.

The participants’ enthusiasm matched the occasion. The discussion was to be the first of several where those who prepared the draft would analyse and explain their handiwork, as well as answer questions. On the platform was P. Tsagaan, Head of the Office of the President. He opened the proceedings with the declaration that posting the draft on the internet so that everybody can study it and then to arrange for a public feedback on the proposals through a discussion like the present was “the true democratic way to enact a law”. He hoped politics and group interests would be kept out of the discussion. Instead, six people, who had worked day and night for many months to prepare the draft, would be allowed a chance to elucidate the philosophy and rationale behind their final product.

The six had been part of a working group, and each of them would cover one aspect of the work. Accordingly, D.Bat-Erdene, of the Association of Mongolian Industrial Geologists, gave a presentation on Prospecting and Exploration of Minerals;Ts.Davaatseren, Director of the Mining Department at the Minerals Authority, spoke on Extraction and Processing; lawyer N.Taivan’s subject was Issue of Licence and Permission to Begin Work; lawyer B.Lhamsuren dealt with Reforming the Mineral Law; lawyer G.Surakhbayar explained the concept of Local Rights; and lawyer D.Munkhtuya covered General Provisions. The contents of their presentations are available on our website and are not being repeated here.

It was now time for the questions to be asked. Private companies and investors had been expressing their strong opposition to proposals in the draft ever since they were published and Tsagaan made it clear he did not wish the present discussion to be just a slanging match. Several participants also seemed keener on expressing suggestions rather than asking questions. Finally, those wishing to join the discussions were divided into four distinct groups: private companies; the civil society; scholars and academics, and representatives of State organisations. The organisers asked each group to meet separately and list their suggestions and comments and then present these at the general meeting.

Broadly speaking, there were more critical suggestions, often cogently put and supported by data, than favourable ones. We, however, do not wish to make any judgement as we believe every suggestion was offered in good faith with the sole aim of getting a better law. Our summary of the views and positions coming out of each group shows how everybody is seeking the best outcome from the opportunity provided by the discussion session. The Office of the President deserves thanks for introducing such a process before a draft can be submitted to be approved into law. We hope this practice becomes standard.

More discussions on the present draft will follow and could very well be more productive. Tsagaan has urged people to judge the draft from a wide perspective and an open mind, instead of sticking to preconceived notions. The interests of the nation take precedence over any group’s, and Tsagaan made it clear the initiators of the law would wait until a comprehensive national consensus was forged on the issue. His appeal to everybody was to approach the draft not merely as a dry document but as an expression of the nation’s collective wish.

Suggestions received from the group of state organisations

- The Mineral Law must be coordinated with laws in force in such areas as Prospecting, Exploration, Extraction, Processing, Small-scale mining, Licence allocation, the Stock Exchange, etc. There must be no amuity or contradiction and it is to be made clear that all other laws would defer to the MineralLaw.

- Too many regulations would merely bind the mining industry to trivial issues. A law cannot hope to cover all details that come up during work. The law must give specific and concise guidelines on general aspects, leaving small things to take care of themselves.

- At present, heavy industrial units come under the Ministry of Industry and Agriculture. So do processing units. The Government Action Plan for 2013-2014 is clear on which Ministry will do what. The draft must reflect any change in Government structure.

- Heavy industries based on minerals must be put under the mining ministry.

- The draft appears to suggest that holders of prospecting and exploration licences get to own the land under their licence. There can be no ownership, and a licence is only for using the land, for a specific purpose.

- Holders of exploration licences find it easy to get a mining licence. This practice should end and mining licences should be allotted through tender, except in cases where the exploration licence is held by a reputable company with a good record of extraction work.

- Proper arrangements have to be made to change many existing laws when the new mining law is approved. It will be best if experts from ministries and agencies work together with the working group that prepared the draft for this.

- The state of the national economy largely depends on mining. Thus the state policy on the mining sector and the mining law have to be complementary. Without such coordination, the likelihood of disputes cropping up will always be there.

- More time should be given to government organisations to submit their suggestions on the draft.

- The State should support exploration work and clear guidelines should be given on how this will be done.

- Natural gas, water, oil, rare earth elements, and radioactive minerals are identified as strategic commodities/minerals. This is untenable as raw material reserves can increase or go down. If those are added or cut, the law is needed to change. The inclusion of a mineral in the list of strategic commodities depends on Parliament, and not on provisions of the law.

- The draft says there will be no strategic mines, but only strategic minerals/commodities. It seems the reason is not to have more than 15 strategic mines. But any mine holding strategic minerals automatically becomes a strategic mine.

- Iron ore should be termed a strategic mineral, and there should be a high tax on its export. Without timely action, all our iron ore will soon be exhausted.

- All the iron ore now exported is unprocessed. We should insist that while this will be allowed in the first three years of mining, from the fourth year, only processed ore or some final product can be exported. Otherwise, we shall find that by the time we build a processing plant, there will be no iron ore left to process.

- Any kind of processing plant needs a huge amount of investment and should be built only after careful consideration of its financial viability. Pre-supply agreements help in the project economics.

- The term Mineral Resources has not been defined, while “high grade mining” is prohibited, and so is total extraction of any resource. There will be disputes if resources are not clearly defined. A mine is defined as a deposit where minerals can be extracted economically, but this is not adequate. There may be mines where extraction is not economical initially, but where profits are made after a certain period. A mine is more than just an economically extractable deposit, and definitions should be accurate to pre-empt legal wrangling.

- There is no provision to regulate small-scale mining. If the law does not have teeth, such mining will continue to defy any regulatory mechanism.

- There is no need for special rules for “Ninja” miners. We have had enough of “Ninjas”, and Mongolia doesn’t have to be the kind of country that encourages such activity.

- The Mineral Resources Authority should be given jurisdiction over all mining-related work by the State Professional Inspection Agency, so that the MRA, at present no more than a registering centre, can exercise control over companies operating irresponsibly. Power to punish is not allocated to that organization. It also has to be brought under the Mining Ministry, so that there is coordination in their work, and information is exchanged regularly.

- Some authority has to be set up to investigate abuse of power by the organisation allocating and cancelling licences. The Administrative Court is not the right place where appeals against this organisation’s decisions can be decided.

- Payment of licence fees is now governed by the Tax Law. This should be changed and fresh and detailed regulations prepared.

- Loopholes in provisions relating to sending samples and material to laboratories abroad for assay should be plugged, so that the permission is not misused to send other important things, maybe of archaeological value, out of the country.

- Companies with local development agreements will build paved roads,schools and kindergartens, taking some burden away from the State. While this is good, the State’s role cannot be restricted to levying and collecting taxes from business entities and leaving local development to the company. We must take care that State organisations retain their capacity and capability.

- The Government will build the Sainshand complex but there is no clarity on where the construction material will come from. Importing cement from China would bring down costs, but would adversely affect the business of domestic cement plants. This matter has to be considered in more detail.

- We need more clarity on issues relating to mining radioactive material, declared a strategic commodity. It is now under the Nuclear Energy Agency, but exploration licences are issued under the Mineral Law, creating anomalies. REE and radioactive minerals are important for national security, and there should be one centralised authority to oversee all issues relating to them -- allocation of exploration and mining licences, transfer of licence, building plants, etc. The Nuclear Energy Law allows tight regulation, and the draft is somewhat cavalier on issues like restricting any one country’s capital investments, which may impinge on national security. It will be better, given the many international conventions that we have signed,to give the Nuclear Energy Agency the sole responsibility for all political and economic issues to do with them, so that a clear policy is followed in all the stages from exploration to processing.

Suggestions received from the Civil Society group

- It’s not enough to give the authority to allocate or withhold a licence to a Soum Citizens’ Representatives’ Khural. Further decentralisation is called for, and the final right should rest with the Bag or Khoroo Citizens’ Representatives’ Khural.

- The final law must refer to the “traditional rights” of people, and not just their economic rights. Mining companies must pay the utmost attention to protect herders’ interests and rights. The OT project sees local people as just poor citizens, and accordingly, its environmental assessment report ignores the needs and rights of herders.

- The list of strategic mines should be open to new inclusions, so as not to restrict the people’s right to have a share of the nation’s wealth found in the highly profitable assets and mines. We should insist on product sharing agreements on strategically important mines and increase the State’s interest in them.

- The draft allows an environmental assessment report to be prepared by a company within three months of receiving the licence. This is against the Environmental Assessment Law. Also, local people’s views have to be considered in preparing the report. This is an existing provision that should remain.

- There should be one single channel for all mineral product export. Norway has achieved very good results from this.

- There should be no more than one processing plant in a Soum, so that the huge economic benefits are shared across the nation. Airag soum in Dornogobi aimag has plans to have as many as five processing plants.

- The law should incorporate specific provisions to ensure information transparency. Both the State and companies must report significant developments to the people. Implementation of the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative must be made compulsory under law, if necessary, by including special provisions.

- Membership of the three professional councils should not be restricted to professionals only. Inclusion of local people will ensure the civil society’s participation.

- The draft should clarify the responsibility of companies in various areas and also the basis on which violations are to be assessed. There should be no scope for any inspector to determine a penalty on an arbitrary understanding of the law.

- Local people should get more power in deciding how reclamation work is to be done. The law should also indicate who will be in the State group to oversee reclamation.

- The draft is silent on waste management. The plan to dispose of heavy waste and chemical waste following mining has to be approved beforehand and the estimated expenses for this waste removal should be put in a special bank account, together with reclamation costs. If the company itself removes the waste, it will get the money back, otherwise, the money will be spent on hiring some professional organisation for the work.

- The draft sets the prospecting deadline at four years, and that for exploration at five. The total of nine years is the same as in the current law, which does not split it. We suggest prospecting and exploration be kept together and the combined deadline made shorter.

- There should be a change in the lines on which the local development agreements should be made. The licence holder should negotiate the agreement with the concerned Soum’s administrative authority, and not the Aimag’s. The present system of an agreement between the company and local citizens does not find a place in the draft, but it is necessary to have local participation at a base level.

- The provision that an application for a licence will be taken as granted if there is no response either way from the local administrative authority with in three weeks is merely a ploy to help licence seekers. There will be a planned flurry of applications, keeping the local administration hopelessly overworked and unable to take a decision on all of them within the stipulated time, thus granting licences by default.

- The criteria for issuing a licence are set out in Articles 22 and 66. However, there is no mention that the decision of the local Citizens’ Representatives’ Khural has to be included in the main decision, making for amuity. All provisions on an issue must be compatible with one another.

- The provisions for cancellation of licence are too indeterminate. There should be a legal basis for cancellation or suspension of licence if a company does “high grade mining”or if local people raise objections to how the project works.

- No company should be allowed to raise capital through an IPO unless and until the Minerals Professional Council approves the mine resources. The draft merely says the company has to inform the State authority.

- The draft allows operational validity of a mining licence to be extended to a total of 60 years, in three instalments of 20 years each. Our view is that every extension should be for a maximum of five years. In Germany such renewal is for only one year.

- The draft does not make it obligatory on an exporter to export only processed or final products, instead of raw ore. Government support for processing plants should also be made mandatory.

Suggestions received from the academics’ and professionals’ group

- Some looking back will give us a better idea of how to go ahead. We need to remember the successes achieved as also the mistakes made in Mongolian mining in the last 90 years, particularly in the 22 years since the end of Socialism, of which the last 10 have been one of intensive development. How much geological and exploration work has been done in this period, how much fresh resource has been discovered, how much of all this has been done with State funds?

Once we do this, we find that Mongolia has never had a comprehensive mining policy. All that the State has done is to have a mining law and make changes in it from time to time. Much better would be for the State to adopt a policy and keep it unchanged for at least 10-15 years. There must be inputs from outside the government before its formal adoption. A mining law will help implementation of that policy and, thus, be free of changes for, again, 10-15 years. This stability is essential, as when companies prepare their feasibility study and raise the capital for investment they know that any change in, say, the tax regimen, can unmake all their plans.

- We notice around 30 unsatisfactory uses of terminology in the draft. It even leaves uncertain what the legal definition of a mineral is. Terms like “waste”, “high grade mining” are too important to be left to individual interpretation. Legal experts should comb through the draft and improve this aspect.

- It is proper that mines should not be kept with the State. Hard work by geological people and exploration companies lead to their discovery and they should rightly claim ownership of the mineral resources.

- Similarly, it is not proper that we shall have no addition to the present list of Strategic Deposits. Strategically important mines are in a category of their own, and the State must have more control over their use.

- Imprecision is a blemish in law. We found 63 provisions that say “can be”, eight that say “until”, three that say “not greater than”, 14 that say “not less than”, and two that say “not more than”. Each of these should be more definite, more exact. There can be no amuity on what can or cannot be done in law. Anything that is left to subjective interpretation will lead to disputes and encourage corruption.

- Floating tenders to allocate licences is a sure prescription for increasing corruption and crime, allowing officials in State organisations and lobbyists for companies to grow fat. Even Russia does not do this. Instead, it publishes direct and clear conditions and chooses the company which offers the most money and promises to develop infrastructure and utilities.

- We should prefer public companies to private or individually owned ones. Listing on the Mongolian Stock Exchange and raising money there would keep them under the gaze ofalert shareholders. Preparation of doctored feasibility studies and declaring exaggerated reserves would cease if the law mandates appointment of professionals, particularly Mongolians, as independent members of the Board of Directors.

- More opportunity should be there for exploration or extractive companies to raise capital on the stock market based on results of 3-4 drilling programmes. This will help cash-starved Mongolian companies to access funds as they work. The draft appears to forcibly discourage foreign investors. The Mongolian people’s interests will not be served if the goal of the mining law is to protect any special interests, be they of the domestic private sector or of foreign investors. Provisions encouraging investment should find a place in the law.

Suggestions received from the companies’ and investors’ group

- Provisions 13, 14, and 15 must be removed. They seek to change the current system of allocating a licence to the company coming first by introducing tenders. This will only give more arbitrary power to the State. The time periods are left vague. The promise to “recompense actual expenses” is against the principles of the market economy. Since 1800, compensation has included payment for lost opportunities in all countries around the world. Most significant is the proposal to transfer the suspended licence to another company through bidding. This is another way of controlled redistribution and should go.

- Processing is outside the ambit of mining and licences for such units should fall under the Licence Law or the Heavy Industry Law. More definite time periods should be given, as just saying 4 or 5 or 20 years merely puts the arbiter in a position of advantage, leading to corruption and crime.

- The proposal on calculation of royalty is too vague and we need something more definitive.

- The draft disallows domestic companies from inviting foreign investment, even though most Mongolian entrepreneurs do not have enough capital to be on their own. This means joint ventures become impossible. The proposed mechanism to raise funds is for companies that receive a mining licence and have begun development work to list on the MSE. This is an untried method and could very well be in effective.

- Many provisions accord special privileges to a State-owned company. If a State-owned company is automaticall yallowed to claim a vacant site next to where its mine is, why should a private company not have the same right? We see a bias against private companies.

- The present regulations on cancellation of licences should remain unchanged. Getting so many State organisations into the act will lead to a bureaucratic monopoly. There will be no end of disputes when 90 provisions are left to the subjective interpretation of one State organisation official or another. These provisions open the doors to corruption and crime.

- State organisations may oversee feasibility studies, working plans, and wage structures but there cannot be any compulsory retroactive approval.

- Provision 72 is about domestic companies using local subcontractors. The principle is good,but it is against a business entity’s freedom to stipulate a definite quantum of the work to be so done. The quality of the service one pays for is important and the work of many domestic subcontractors does not meet the standards.

- If the draft limits state participation in the 15 Strategic Mines, why cannot this be done totally?

- The draft says any tender process can be stopped at citizens’ request but does not indicate what the acceptable grounds of the objection should be or specify who deals with this problem and how. The law should mention specific grounds and a decision cannot be left to individual whim.

- There should be specific grounds and limits to the culpability of a company’s executives and officials. These cannot be left to be determined by interested people with the means.

- We do not think it is a fully satisfactory draft. Its underlying principles are suspect, the group that worked on it should have had wider representation, and the views of several constituents of the sector should have been ascertained. As it stands, it cannot claim widespread acceptance.

- Why do we need permission to start operations, once we have been granted a licence? A secondary permission even after the primary one smacks of needless bureaucratic control.

- A review of the environment-related provisions is called for. Both the nature of the mechanism and how it will work have to be made clear. The legal imperative of depositing in advance 100 percent of the estimated reclamation costs is a burden and it also releases companies from the commitment to do the actual reclamation work.